How Should We Regulate Child Labor?

March 15, 2023 by Katie Jones

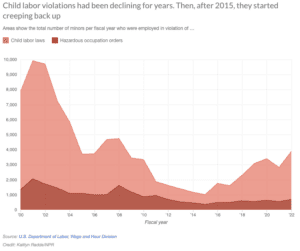

On March 6, Arkansas Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders signed into law the Youth Hiring Act, a law that, among other things, allows children between the ages of nine and 16 to be hired without the need for an employment certificate to be filed with the state. Under previous state law, an employment certificate was required to be filed with the state providing proof of age, the work schedule and description, and the consent of the child’s parent or guardian.1 In the past few months, lawmakers in Iowa and Ohio have also proposed legislation that would reduce requirements for youth seeking work.2 READ: “The Good and the Bad of Iowa’s Bill That Would Bring Big Changes to Child Labor Laws,” from the Des Moines Register READ: “Bill to Extend Working Hours for Ohio Teens Reintroduced by Lawmakers,” from News 5 Cleveland Proponents of bills like the Youth Hiring Act believe that removing restrictions on child labor would encourage more young people to work and decrease the difficulty businesses have had hiring recently due to record-low unemployment rates. Some lawmakers, such as Iowa State Senator Lynn Evans, have cited the benefits of young people learning the value of work.3 In Arkansas, Governor Sanders provided rationale for removing the certificate requirements. Her spokesperson, Alexa Henning, shared that requiring parents to get permission for their child to work is an additional burden when businesses are required to follow child labor laws in the U.S. regardless of the certificate.4 Business interest groups, including the National Federation of Independent Businesses, have supported the Ohio bill.5 Opponents of these bills have cited statistics indicating that the wellness of young workers could be in jeopardy if they are scheduled for longer hours.6 Children may take on more work than they can handle in order to provide financial support for their families. Randy Zook, CEO of the Arkansas State Chamber of Commerce, voiced his opposition to the Arkansas bill. “The primary thing kids that age need to be focused on is graduating from high school,” he said. “We are afraid this will encourage kids who are under 16 to pursue more work time than school time.”7 These bills have worked their way through state legislatures at the same time that several eye-opening investigations into child labor practices have exposed egregious violations. In July 2022, Reuters published an investigation that documented children as young as 12 working at four Hyundai and Kia subsidiaries.8 On February 25, New York Times reporter Hannah Dreier released the findings of her investigation into the labor conditions of migrant children, interviewing more than 100 children in 20 states.9 Children interviewed included a 15-year-old Guatemalan girl who packages Cheerios, a ninth-grader working 14-hour shifts at a sawmill in South Dakota, and middle schoolers working in bakeries. These working conditions violate federal laws that limit the jobs children can work and the hours and times they can be scheduled.10 The New York Times and Reuters investigations point to a willingness of some businesses in manufacturing, construction, hospitality, and food processing, among others, to turn a blind eye to clear violations of the law and exploit those in vulnerable situations as evidence for increased restriction and oversight of child labor. Child labor violations had been declining for years. Then, after 2015, they started creeping back up.

On March 6, Arkansas Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders signed into law the Youth Hiring Act, a law that, among other things, allows children between the ages of nine and 16 to be hired without the need for an employment certificate to be filed with the state. Under previous state law, an employment certificate was required to be filed with the state providing proof of age, the work schedule and description, and the consent of the child’s parent or guardian.1 In the past few months, lawmakers in Iowa and Ohio have also proposed legislation that would reduce requirements for youth seeking work.2 READ: “The Good and the Bad of Iowa’s Bill That Would Bring Big Changes to Child Labor Laws,” from the Des Moines Register READ: “Bill to Extend Working Hours for Ohio Teens Reintroduced by Lawmakers,” from News 5 Cleveland Proponents of bills like the Youth Hiring Act believe that removing restrictions on child labor would encourage more young people to work and decrease the difficulty businesses have had hiring recently due to record-low unemployment rates. Some lawmakers, such as Iowa State Senator Lynn Evans, have cited the benefits of young people learning the value of work.3 In Arkansas, Governor Sanders provided rationale for removing the certificate requirements. Her spokesperson, Alexa Henning, shared that requiring parents to get permission for their child to work is an additional burden when businesses are required to follow child labor laws in the U.S. regardless of the certificate.4 Business interest groups, including the National Federation of Independent Businesses, have supported the Ohio bill.5 Opponents of these bills have cited statistics indicating that the wellness of young workers could be in jeopardy if they are scheduled for longer hours.6 Children may take on more work than they can handle in order to provide financial support for their families. Randy Zook, CEO of the Arkansas State Chamber of Commerce, voiced his opposition to the Arkansas bill. “The primary thing kids that age need to be focused on is graduating from high school,” he said. “We are afraid this will encourage kids who are under 16 to pursue more work time than school time.”7 These bills have worked their way through state legislatures at the same time that several eye-opening investigations into child labor practices have exposed egregious violations. In July 2022, Reuters published an investigation that documented children as young as 12 working at four Hyundai and Kia subsidiaries.8 On February 25, New York Times reporter Hannah Dreier released the findings of her investigation into the labor conditions of migrant children, interviewing more than 100 children in 20 states.9 Children interviewed included a 15-year-old Guatemalan girl who packages Cheerios, a ninth-grader working 14-hour shifts at a sawmill in South Dakota, and middle schoolers working in bakeries. These working conditions violate federal laws that limit the jobs children can work and the hours and times they can be scheduled.10 The New York Times and Reuters investigations point to a willingness of some businesses in manufacturing, construction, hospitality, and food processing, among others, to turn a blind eye to clear violations of the law and exploit those in vulnerable situations as evidence for increased restriction and oversight of child labor. Child labor violations had been declining for years. Then, after 2015, they started creeping back up.  On February 27, two days after the New York Times report, President Joe Biden’s administration unveiled several policies that will be implemented to address the nearly 70 percent rise in child labor violations that has taken place from 2018-2022.11 The plan includes the creation of a new task force, targeting industries that have a history of violations, and advocating for heavier penalties and more funding for oversight.12 Congressional Democrats largely support the White House proposal. Republicans, meanwhile, say the Department of Health and Human Services is to blame for the child labor crisis because the Biden administration has loosened regulations regarding the support of migrant children.13 One third of migrant children who have been recorded by HHS now cannot be reached by government officials.14 Meanwhile, some states, such as Nebraska, have renewed their support for child labor protections. On January 5, Nebraska State Senator Carol Blood proposed a resolution that would make Nebraska the 29th state to ratify the Child Labor Amendment of 1924, an amendment to the Constitution that, if passed, would specifically allow Congress to regulate the labor of minors.15 Discussion Questions

On February 27, two days after the New York Times report, President Joe Biden’s administration unveiled several policies that will be implemented to address the nearly 70 percent rise in child labor violations that has taken place from 2018-2022.11 The plan includes the creation of a new task force, targeting industries that have a history of violations, and advocating for heavier penalties and more funding for oversight.12 Congressional Democrats largely support the White House proposal. Republicans, meanwhile, say the Department of Health and Human Services is to blame for the child labor crisis because the Biden administration has loosened regulations regarding the support of migrant children.13 One third of migrant children who have been recorded by HHS now cannot be reached by government officials.14 Meanwhile, some states, such as Nebraska, have renewed their support for child labor protections. On January 5, Nebraska State Senator Carol Blood proposed a resolution that would make Nebraska the 29th state to ratify the Child Labor Amendment of 1924, an amendment to the Constitution that, if passed, would specifically allow Congress to regulate the labor of minors.15 Discussion Questions

- What might be some of the benefits to loosening child labor laws? What might be the drawbacks?

- If the Department of Labor is successful in significantly reducing child labor violations, what might be the outcomes for young workers? For businesses?

- Which entity or entities have the most responsibility to regulate children in the workforce: the federal government, state and local governments, businesses, or parents?

- What policies, if any, do you think governments should enact in order to promote the best outcomes for youth and child workers?

As always, we encourage you to join the discussion with your comments or questions below. Sources