Should We Decarcerate?

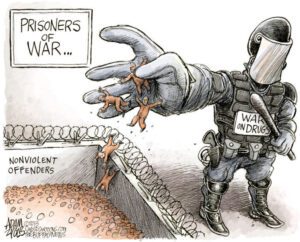

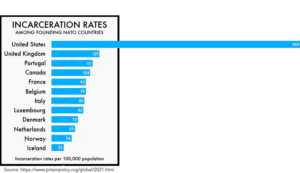

Since the start of the War on Drugs, the United States has adopted and enforced policies that have led to mass incarceration, with nearly half of all incarcerations due to drug crimes.1 According to the Prison Policy Initiative, the rate of incarceration in the United States outpaces every other nation on earth, and it comes at a high cost: “With nearly two million people behind bars at any given time, the United States has the highest incarceration rate of any country in the world. We spend about $182 billion every year—not to mention the significant social cost—to lock up nearly 1% of our adult population.”2

The question is whether these costs are worth it.

Some scholars say no, pointing to dehumanizing effects and power imbalances created by mass incarceration. Kelly Lytle Hernández, a professor of history, African American studies, and urban planning at the University of California Los Angeles, argues that the racial disparity in mass incarceration is intended to control specific communities: “Incarceration operates as a means of purging, removing, caging, containing, erasing, disappearing, and eliminating targeted populations from land, life, and society in the United States.”3

But while there are a growing number of calls to end mass incarceration, there are those who believe the high rate of incarceration is a good and necessary thing. Barry Latzer, a retired criminal justice professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice CUNY, argues that mass incarceration was a rational and—all things considered—beneficial response to the “crime wave” between the 1970s and 1990s, when crime rates were far higher than they are today.4

Rafael Mangual, head of research at the Manhattan Institute, argues that the push to reduce incarceration levels will lead to the release of people who are likely to reoffend in the communities already most vulnerable to crime, unintentionally causing harm to the very communities prison reform advocates intend to help.5

WATCH: The Heritage Foundation’s Charles “Cully” Stimson Interviews Barry Latzer and Rafael Mangual

Others, like political scientist Charles Murray of the American Enterprise Institute, are even more blunt: “We figured out what to do with criminals. Innovations in policing helped, but the key insight was an old one: Lock ’em up.”6 Retired UCLA Professor James Q. Wilson concludes, “Putting people in prison is the single most important thing we’ve done [to decrease crime].”7

The rise of mass incarceration did, after all, parallel the reduction in crime rates.

This belief in the beneficial impact of mass incarceration has been challenged in recent years. Don Stemen, a professor of criminal justice and criminology at Loyola University Chicago, summarizes the conclusions of the Prison Paradox project: “It may seem intuitive that increasing incarceration would further reduce crime: incarceration not only prevents future crimes by taking people who commit crime ‘out of circulation’ (incapacitation), but it also may dissuade people from committing future crimes out of fear of punishment (deterrence). In reality, however, increasing incarceration rates has a minimal impact on reducing crime and entails significant costs.”8

Numerous studies have concluded that incapacitation and deterrence have led to only marginal (6-12 percent) reductions in property crime and are responsible for as little as zero percent of the reduction in violent crime over the past two decades. These studies attribute the reduction in crime since the 1990s to other social and economic factors, including “increased wages, increased employment, increased graduation rates, increased consumer confidence, increased law enforcement personnel, and changes in policing strategies.“ Some scholars have even connected the decrease in crime since the 1990s with the transition from leaded to unleaded gasoline between 1992 and 2002.9

Regardless of one’s position on the effectiveness of incarceration on crime rates, what is not in dispute is that the United States locks up a higher number of its own citizens than any other country in the world, and that there is an unmistakable, decades-long correlation between low graduation rates and mass incarceration.10 Those who warn against the threats of decarceration do so on the belief that when those who have been convicted of crimes are released, they are very likely to commit more crimes in the future and end up back in jail or prison. The national rate of return to the criminal-legal system after incarceration—called “recidivism”—is 76.6 percent.11

There are others, however, who point to a way to reduce recidivism dramatically: education and mentorship programs, both inside prison and working with those who have returned from incarceration. In Part 3 of this series, we will examine the impact of prison education programs which attempt to reverse the “school-to-prison pipeline.”

Discussion Questions

- Do you think incarceration should primarily be a tool for punishment or rehabilitation?

- What does rehabilitation mean? What should be the standard for returning from incarceration?

- Do you think the level of incarceration in the United States is a problem? If not, why not? If so, how high a priority is this issue for you?

Related Posts

- Reversing the “School-to-Prison Pipeline”? Part 1: Defining the School-to-Prison Pipeline

- What Do “Defund the Police” and “Police Abolition” Mean? And What Do They Not Mean?

- Criminal Justice Reform: The First Step Act

- Should Public College Be Free?

- The Debate Over School Resource Officers and the #CounselorsNotCops Campaign

As always, we encourage you to join the discussion with your comments or questions below.

Sources

Featured Image Credit: Adam Zyglis

[1] Federal Bureau of Prisons: https://www.bop.gov/about/statistics/statistics_inmate_offenses.jsp

[2] Prison Policy Initiative: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/profiles/US.html#:~:text=With%20nearly%20two%20million%20people,1%25%20of%20our%20adult%20population.

[3] Lytle Hernandez, Kelly. “City of Inmates: Conquest, Rebellion, and the Rise of Human Caging in Los Angeles, 1771-1965.” 2017.

[4] Heritage Foundation: https://www.heritage.org/crime-and-justice/event/the-myths-mass-incarceration-and-overpolicing

[5] Ibid.

[6] The Sentencing Project: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/scans/sp/DimRet.pdf

[7] Ibid.

[8] Vera Institute of Justice: https://www.vera.org/downloads/publications/for-the-record-prison-paradox_02.pdf

[9] Vera Institute of Justice: https://www.vera.org/downloads/publications/for-the-record-prison-paradox_02.pdf

[10] Bureau of Justice Statistics: https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/ecp.pdf

[11] Harvard Political Review: https://harvardpolitics.com/recidivism-american-progress/

What Do People Mean When They Talk About the School-to-Prison Pipeline?

What Do People Mean When They Talk About the School-to-Prison Pipeline?  Franchise teams with Close Up to send high school students on team plane…Johnson’s essay was what got him to Phoenix Sky Harbor Airport on Wednesday morning, one of 260 students chosen — based on their essays — to take part in the second annual Civics Matter Arizona trip to Washington D.C. Pairing with the Close Up Foundation…

Franchise teams with Close Up to send high school students on team plane…Johnson’s essay was what got him to Phoenix Sky Harbor Airport on Wednesday morning, one of 260 students chosen — based on their essays — to take part in the second annual Civics Matter Arizona trip to Washington D.C. Pairing with the Close Up Foundation…