The case of Brackeen v. Haaland is currently facing the U.S. Supreme Court. The case calls into question the constitutionality of the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) of 1978. The two major questions in the case are: (1) Is the ICWA unconstitutional on the basis of racial discrimination because of its favoring of Native families in the adoption of Native children? (2) Is the ICWA an overreach of Congress’ powers because it impedes the right of states to set the standards for placement of children in their child welfare systems?1

The case of Brackeen v. Haaland is currently facing the U.S. Supreme Court. The case calls into question the constitutionality of the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) of 1978. The two major questions in the case are: (1) Is the ICWA unconstitutional on the basis of racial discrimination because of its favoring of Native families in the adoption of Native children? (2) Is the ICWA an overreach of Congress’ powers because it impedes the right of states to set the standards for placement of children in their child welfare systems?1

To understand Brackeen v. Haaland, it is imperative to first understand what the ICWA is and how it came to be enacted. That is what we will focus on in this first of a series of blog posts.

What Is the ICWA? Why Does It Exist?

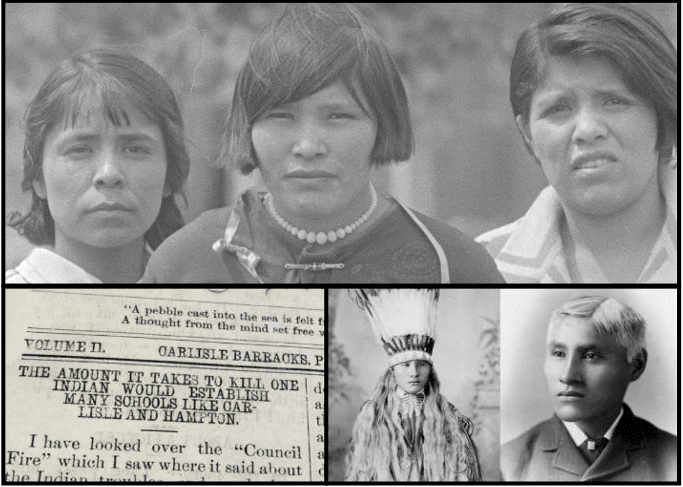

The practice of removing Native children from their tribes started as far back as the birth of the United States (and some would argue before that). The first incidence of Indian child removal occurred during the Revolutionary War as a way to conquer Native nations.2 It was generally believed that Native people needed to be “civilized” and assimilated (or conformed and adapted) to the “American” way of life. To achieve this, the U.S. government set up more than 350 boarding schools across the country, which were designed to systematically strip tribal culture from the Native children who were forced to attend them.3 The schools pushed Christianity, required the use of English, and restricted Native children from speaking their language, wearing cultural dress, using cultural practices, or even using their Indian birth names.4 The first of these boarding schools, the Carlisle School, was founded in 1872 by U.S. Army Captain Richard Henry Pratt. Pratt’s motto for assimilation was the now well-known phrase: “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”5 All Native boarding schools to follow would adopt Pratt’s model.6

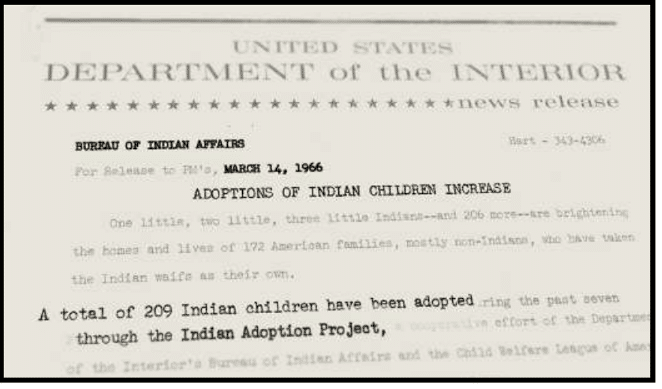

When the Great Depression hit, there were fewer resources to go around, so the government began to close the boarding schools and created the Indian Adoption Project in their place. In this new program, which ran until the 1950s, Native children were forcibly removed from their families and placed up for adoption to white families who would assimilate them into “American” culture. The removal of children was justified by a loose definition of neglect, which was often based on the interpretation of social workers who were untrained in Native culture and who used an Anglo-Saxon lens for assessing family structure. In Native communities, for example, it was not uncommon for multiple extended families to live in the same house; it was very common to have a nontraditional family structure. The Indian Adoption Project used this difference in family structure to force families into giving their children up for adoption.7 By 1974, research found that between 25 percent and 35 percent of all Native children in the United States were in foster, adoptive, or institutional homes away from their tribes.8 These family separations had a devastating impact on Native culture and communities as a whole.

In the 1960s and 1970s, social movements began to bring light to the issue of Native separation. Eventually, Congress decided to address the issue. After an investigation, Congress reported that “an alarmingly high percentage of families are broken up by the removal (often unwarranted) of their children by nontribal public and private agencies and an alarmingly high percentage of such children are placed in non-Indian institutions.”9 The report also found that state governments “often failed to recognize the essential tribal relations of Indian people.”10

In response, Congress passed the ICWA in 1978, declaring “that it is the policy of this Nation to protect the best interests of Indian children and to promote the stability and security of Indian tribes and families by the establishment of minimum Federal standards for the removal of Indian children from their families.”11

The ICWA establishes guidelines for how states should handle issues regarding Native children in the child welfare system, including cases of child abuse and neglect, foster and adoption cases, removal, and out-of-home placement.12 The law gives Native communities a seat at the decision-making table when placing Native children in homes. And not unlike the traditional child welfare system, it prioritizes keeping Native children with members of their tribe whenever possible. The goal of the law is to keep families together, to protect the rights of Native people to govern themselves, and to support their cultural independence following decades of forced separation and assimilation attempts by the U.S. government.

Although the attempts to assimilate and erase Native culture in the United States ultimately failed (proven by the fact that there are more than 500 sovereign Native nations recognized in the country today), it does not mean the generations of forced removal have not had a lasting impact on these communities.13 The next part of this series will discuss the complex issue of the ICWA adoption issues in modern times and the Brackeen v. Haaland Supreme Court case that questions its constitutionality.

Discussion Questions

- What, if anything, did you learn from this post that you had not known about Native history previously?

- What, if anything, surprised you in what you read? What about it moved you?

- How do you believe Congress should have handled the issue of Native separation?

- Do you think the creation of the ICWA was the right decision? Was it enough? Was it the best way address to the problem? Why or why not?

- Should the status of a child as Native American impact who can adopt or not adopt him/her? Why or why not?

- How does this controversy connect to other issues you have heard in the news? In history?

- Do you think the ICWA should remain in place? Why or why not?

Other Resources

See the full detailed report from Congress on the ICWA.

For an in-depth investigation of this case from an indigenous perspective, listen to the second season of the podcast This Land, hosted by Rebecca Nagle.

As always, we encourage you to join the discussion with your comments or questions below!

Sources

Featured Image Credit:Vision Maker Media

[1] SCOTUSBlog: https://www.scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/brackeen-v-haaland/

[2] Huffington Post: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/indian-child-welfare-act-adoption_n_5dcb1fe8e4b098093b026b83

[3] George Mason University Social History Project: http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/4929

[4] Huffington Post: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/indian-child-welfare-act-adoption_n_5dcb1fe8e4b098093b026b83

[5] Dickinson.edu: https://carlisleindian.dickinson.edu/teach/kill-indian-him-and-save-man-r-h-pratt-education-Native-americans

[6] Digital History: https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtid=2&psid=3505

[7] U.S. House of Representatives, 1978 Report on Establishing Standards for the Placement of Indian Children in Foster or Adoptive Homes to Prevent the Breakup of Indian Families and for Other Purposes: https://www.narf.org/nill/documents/icwa/federal/lh/hr1386.pdf

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute: https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/25/1902

[12] ChildWelfare.gov: https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/systemwide/diverse-populations/americanindian/icwa/

[13] Native Times: https://www.Nativetimes.com/archives/46-life/commentary/14059-truth-and-reconciliationkill-the-indian-and-save-the-man

Last week, Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen, a former project manager for their Civic Integrity team, testified before Congress and criticized the social media company as a dangerous, unchecked force that was “buying its profits with our safety.”1 Haugen faulted the senior leadership at Facebook for identifying safety risks yet refusing to make the necessary changes to address them. “I’m here today because I believe Facebook’s products harm children, stoke division, and weaken our democracy,” she told the committee, before providing a detailed account of the inner workings of the company.2

Last week, Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen, a former project manager for their Civic Integrity team, testified before Congress and criticized the social media company as a dangerous, unchecked force that was “buying its profits with our safety.”1 Haugen faulted the senior leadership at Facebook for identifying safety risks yet refusing to make the necessary changes to address them. “I’m here today because I believe Facebook’s products harm children, stoke division, and weaken our democracy,” she told the committee, before providing a detailed account of the inner workings of the company.2 The Supreme Court begins its new term on the first Monday in October, a tradition that dates back to 1917.1 This year, that meant yesterday, Monday, October 4. In the term ahead, the Court is set to take up many key constitutional and legal issues. For the Supreme Court term preview, Close Up is offering a

The Supreme Court begins its new term on the first Monday in October, a tradition that dates back to 1917.1 This year, that meant yesterday, Monday, October 4. In the term ahead, the Court is set to take up many key constitutional and legal issues. For the Supreme Court term preview, Close Up is offering a