In this week’s blog post, we will explore an idea that is gaining some traction in the United States: term limits for members of Congress.

New Kids on The Very, Very Old Block

After attending orientation classes (yes, those are a thing) and being sworn in, freshman representatives and senators will take their seats next to members that include Senator Patrick Leahy, D-Vt., and Representative Don Young, R-Alaska, who have served in Congress for 44 and 46 years, respectively. For those doing the math, Senator Leahy is currently serving his eighth term in the Senate and Representative Young just won his 23rd term [1]. Yet neither member touches retired Representative John Dingell’s, D-Mich., record 59 years and 21 days in the House, standing for election no less than 30 times.

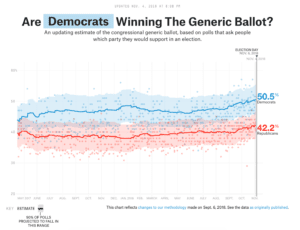

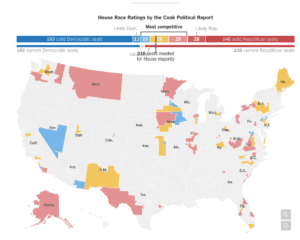

Since 1964, incumbent senators typically have an 80 percent chance of being reelected; representatives average closer to 95 percent [2]. There are a number of factors that account for the incumbent advantage. Incumbents usually have more name recognition, more campaign money, and a congressional record to point to. With those factors in place, the most likely reason a member of Congress is not reelected is either retirement or death (although that isn’t always a deal-breaker; see Mel Carnahan in 2000 [3]).

The prevalence of career legislators has led some to question whether or not the absence of term limits in the House and Senate is at odds with Congress’ role as a truly representative body. Besides, we’ve limited the terms of presidents, so why not do the same for members of Congress?

The biggest obstacle to implementing Congressional term limits is the Constitution itself. The only term limit that has been imposed has been on the presidency through the 22nd Amendment. Therefore, a precedent has been established that another amendment would be required to impose term limits on representatives and/or senators. The process of passing a constitutional amendment is arduous to say the least, but the most fundamental obstacle would be that Congress itself has to approve it. In a legislature dominated by career legislators, it is unlikely they would vote to limit themselves.

Amendments Aside, What Are the Arguments?

Those in favor of term limits argue that we should impose them on members of Congress for the very same reason we impose them on the president: to create a check on power. Congresspeople wield tremendous power and influence. They are the only 535 citizens (out of 320 million) who actually get to vote on our laws. They shape government policy, create budgets, confirm presidential appointments, and declare war. Yet holding power for lengthy periods makes members of Congress less like elected representatives and more like a political aristocracy—one that is secluded in a “Washington Bubble.” Some Americans feel that by spending so much time in Congress, members become detached from their constituents. And when they can take their reelection for granted, members are less inclined to represent their constituents’ interests. Some also argue that when a member of Congress has been in office longer than most of his or her constituents have been alive, that member is out of touch with the needs and changing sensibilities of his or her district.

So the logic seems pretty sound there. Are there any arguments for keeping things as they are? Well, yes.

Others believe that the absence of term limits protects the power of the legislative branch as a check on the executive branch. Take Representative Young and Senator Leahy, for example. Both have been in power since Watergate and have seen eight presidents come and go during their tenure. Without term limits, they are able to legislate beyond the scope of one administration. Furthermore, the responsibilities of a member can be enormously complicated. It can take years to forge relationships and master the rules that govern Congress.

Others caution against the creation of a lame-duck Congress. A “lame-duck” describes an elected official who has not been reelected but is serving out the remainder of his or her term. This period is sometimes seen as problematic, as those who will remain in power beyond the lame-duck period are less likely to work with lame-ducks on new policies since they’ll soon be dealing with replacements who may want different things. As it stands, there are 30 lame-duck representatives and a handful of lame-duck senators for the next two months. With term limits, there could be hundreds of lame-duck members for years at a time.

Discussion Questions

- Should members of Congress be subject to term limits? How many terms should they be allowed to run for?

- Do you think the incumbent advantage presents a problem for true representation in Congress? Would term limits solve this problem? What other changes might make races more competitive?

- Currently, the Constitution requires representatives to be at least 25 years old and senators to be at least 30. Rather than enacting term limits, some have suggested imposing a mandatory retirement age for members of Congress or a maximum age of election. Do you agree with this? Does this idea present problems of its own?

- The 22nd Amendment prohibits the president from serving more than two full four-year terms, even non-consecutively. Some have argued that the absence of a limit on consecutive terms for members of Congress is the true problem with the system. They suggest that members of Congress be allowed to serve unlimited terms, but that after a number of consecutive terms, they be required to stand down for at least one term. For example, a senator could run for two consecutive six-year terms, be required to stand down, and then run again six years later. What are some of the advantages and disadvantages to this suggestion?

Sources:

Image credit: Political Cartoon by Gary Varvel, IndyStar.com

[1] Estepa, Jessica. “Alaska’s Don Young to Become Most Senior Member of Congress After Conyers’ Retirement.” USA Today. 5 Dec. 2017. Web. 26 Nov. 2018.

[2] OpenSecrets.org. “Reelection Rates Over the Years.” Web. 26 Nov. 2018.

[3] Balz, Dan, and Mike Allen. “Mo. Gov. Killed in Plane Crash.” Washington Post. 17 Oct. 2000. Web. 26 Nov. 2018.